The QGIS documentation team is struggling and needs help. This has been known for a while. The much harder question is “How do we help a mostly volunteer community?”.

Reading time: 25 minutes

Summary

Many have tried to help QGIS docs, with limited success. I’ve collated insightful quotes from a bunch of their stories and then postulate solutions. Surprisingly, the biggest problem isn’t a lack of tech writers or complicated tools (although they are factors).Problems centre around:

- Poorly capturing community good-will and offers of assistance;

- A lack of direction;

- Struggling to keep up with a rapidly evolving software baseline;

- Insufficient writing expertise;

- A high technical barrier to entry;

- Documentation and training being generated outside of the core project;

- Awkward documentation tools and processes.

- Define and evangelise a vision and roadmap.

- Prioritise funding and lobby sponsors to resource the vision.

- Implement an information architecture review.

- Sustain a community evangelist/coordinator to attract and nurture a broader doc community.

- Sustain a trained technical writer to amplify the quality and effectiveness of the community.

- Attract external docs back into the core.

- Ask the greater open-source community to address the usability of documentation tools and reduce the technical barrier to entry. Adopt improvements as they are developed.

- Align with best the practices evolving within TheGoodDocsProject.

Observations

The challenge

As one of OSGeo’s Season of Docs administrators, I’ve been observing the QGIS documentation community for months. The Open Source Geospatial Foundation (OSGeo) was allocated two tech writers and we probably should have allocated one to QGIS. However, I recommended they work on GeoNetwork and OSGeoLive instead. I was concerned by:- How daunting QGIS doc challenges were,

- A lack of clear direction within the QGIS docs project,

- The brief three-month window for Season-of-Docs, and

- The high risk that the writers’ efforts might not achieve tangible outcomes.

The big challenge for QGIS is aggregating external content into the core docs from lots of satellite communities. It would be a huge win to get it done, but also very risky as it requires coordination and collaboration from so many external volunteers.Harrissou added:

It's unfortunate to not assign a senior writer to QGIS. I was personally envisioning [Season of Docs] as a catalyzer, an opportunity to trigger mobilisation of the writing community, and to teach us actual and best practices. And maybe that experience would confirm to us that we need the profile [of person] you propose later.So what is lacking, and what can be improved?

Kudos to the volunteers

Firstly, I’d like to acknowledge the value provided by QGIS documentation volunteers and help they provide to newbies who reach out. QGIS has a solid baseline of docs and dedicated but under-resourced volunteers. They face a difficult job keeping up with the more active, much larger, and better-resourced developer community. I don’t think external people appreciate the difficulty of the documentation challenge.Season of Docs

Before Season-of-Docs’ writing period officially started (September 2019) we’d already attracted plenty of latent interest:- A spin-off GeoNetwork documentation group of 4+ volunteers was meeting fortnightly. (Swapnil, a senior tech writer supports this team, as part of Season-of-Docs.)

- A spin-off GoodDocsProject, with 5+ senior tech writers, are creating best-practice templates and writing instructions for documenting open-source software.

- QGIS and GeoNetwork quickstarts were updated to the latest 13.0 OSGeoLive release. (Felicity is updating 50+ quickstarts for Season-of-Docs.)

Piers, small company, creating training material

Piers Higgs is CEO of a Gaia Resources, a small environmental consulting company. He and his team have developed QGIS training material which they publish for free as videos, a manual and data package. Piers notes:- The thing I find strange is how many people are using our course now - there are people from all around the world now. Most of them aren't actually enviro's either - they are just people wanting any sort of resource to help them get into QGIS.

Alexandre Neto noted:

- Because we don't have many writers (we have two very active people), it's quite hard to allocate [time for] that “king of merge” into what we already have. It looks like no one has interest in it, but it's not really the case. What we would prefer is to see companies create new sections, improve and reuse what we have in the training manual.

- Yep, but how to tap this potential is pretty hard. Unless you have a TARDIS, or a cloning machine?

- This pretty much says why I can't get into this. I don't have the bandwidth and much of my drive is taken up running the business. The personality - well, Cameron, you have spades of that ;)

- I did find the whole thing really hard to actually understand what was needed and who was doing what. I guess being "outside the camp" for most of the QGIS stuff these days has made me realise how hard it is to find my way back in again.

- So it's one thing to have a bunch of time-poor people who are interested, let's assume we don't have a TARDIS or cloning machine to fix that. I did find that trying to work out what was going on and what Season-of-Docs is, who's doing what, etc was just too big a beast to deal with. It was an effective barrier to entry for someone new, and it's one of the reasons Cameron found it so hard to engage me - I had to keep asking him for clarifications on what all the lists are, where the documents are, who's who in the zoo, etc. It's just a little bit... chaotic. I will readily admit I lean towards OCD tendencies, but being time poor, time spent trying to understand what is going on is an effective barrier to entry. It became "too hard" very quickly.

- [Capturing offers of assistance and supporting and encouraging new volunteers] are things as a community we do pretty badly.

- My interactions with the main QGIS developers etc hasn't been very frequent, but it's been reasonable.

- ... So I think remembering everyone is a volunteer and will have different motivations is really important. I used to run a volunteer GIS group and keeping up ways in which time poor people can be involved is key - e.g. writing a chapter is a big ask, but editing or testing it might be smaller and easier for time poor people. Food for thought.

Andrew, power user, starting to help with docs

Andrew Jeffrey is a power QGIS user, and a bit more. He is not a programmer and is giving to QGIS through docs, coordinating a regional user group and qgis events. (Other potential volunteers have a similar profile.) Andrew painted a practical vision about how QGIS docs can be improved and proceded to write a getting started guide for the new users he’d been helping, and followed up with a QGIS quickstart for the OSGeoLive project. Andrew is the sort of person you’d want to encourage and support.Andrew’s comments are revealing:

- I feel this review [of QGIS docs] was started with the meetings you coordinated at the start of the Season-of-Docs process Cameron and then lost momentum because no one took the lead when you started to focus on other things. I did try to rally people for the OSGeolive quickstart amendments but quickly lost interest in continually asking for input with no response.

- I haven't given a whole lot - but would like to do more. Things that stop me: What’s a priority? Docs, training material, screenshots? It would be helpful if a more senior doc mentor was able to say “this is the low hanging fruit” “that is a great way to get started”.

- The help I have received from QGIS doc folks has been good and available when I ask for it. The support in terms of sharing contributions via participants in the Season-of-Docs has been sporadic, but I understand everyone has time constraints and other commitments. Also even before tech writers were assigned to projects I was asking the list for feedback on documentation and received nothing. So my enthusiasm for the Season-of-Docs has dropped off because I didn't feel like I was getting as much out as I was putting in.

Jared, a tech writer

Jared Morgan is a senior tech writer, curious about open source, who volunteered to help out. He started reviewing QGIS docs and received feedback from core contributors (Harrissou and Matteo). Alexandre noted that he missed seeing Jarad’s feedback. Unfortunately, this initiative hasn’t appeared to be sustained. It appears there hasn’t been sufficient bandwidth to nurture and sustain the goodwill.Charlie, university courses

There were a bunch of offers from GeoForAll university members, suggesting that their tertiary training material be used. For instance, we could update the comprehensive GeoAccademy courses which are still based on the old QGIS 2.8 version. Unfortunately, the initial enthusiasm didn’t translate into tangible action. From my perspective, there appeared to be a very high barrier to entry. How can we help all these disparate organisations and fragmented initiatives to collaborate on a common base of material which is brought into the core QGIS docs? How can they become less brittle, so material continues to be updated when program funding finishes?Professor Charlie Schweik suggested developing training material and textbooks in conjunction with universities, possibly making use of OpenStax. I’d suggest that his suggestion be aligned with maintaining core QGIS material, rather than creating a parallel initiative, and that the common material can be retasked for various educational courses.

Andreas, cataloging doc team challenges

The QGIS docs team discussed many of the challenges they are facing. Andreas Neumann summarises many of these:- I agree that the documentation task seems to be overwhelming and might also be daunting for newcomers, volunteers and even paid people. I also agree that the team is under-resourced. … We already knew this. … it would be encouraging to hear more suggestions for how to improve the situation.

- Should the team focus on smaller chunks/goals in order to have better progress and a better success feeling?

- Are the tools too complicated?

- Is there not enough information provided by developers or organizations who fund new features?

- Another observation I have is that there is an awful lot of documentation about QGIS out there on the web, spread into many personal blog websites, company blog posts and news sites, youtube movies, social media posts, etc. etc. However, all of this vast and de-centralized information doesn't end up in our central documentation.

Anita, Nathan, tools and process limitations

Working out how to bring the world’s QGIS documentation back into the core looks to be a core challenge for QGIS. Anita Graser’s response provides insights:- I tried [putting my doc updates into the core] but something is keeping me from doing it regularly. Thinking about it, reasons for me include:

- It's not always possible to simply copy a blog post to the documentation. The expected style (as in wording) of the text is different. The text should fit into the bigger picture. This often means a significant rewrite.

- Maybe just me but: I'm always uncertain of how to add figures and links correctly so that they are not broken in the built documentation.

- Lack of immediate feedback: When I post on a blog, the content is immediately online and - as feedback comes in - it's possible to make adjustments quickly. The above Pull Request was open for a month. (There were a lot of good discussions going on but it might feel more motivating to publish more quickly and improve incrementally).

So the last two points come down to the process we currently have in place. Coming from a platform (Wordpress) where I can immediately see and verify the final results, the qgis.org documentation system makes me feel less certain about the quality of my edits and it takes much longer until corrections are visible online. (I know that I could build the documentation locally on my machine. I've tried with Richard's help in the past and failed to set it up on my machine.)

I personally find some of the technical issues as quite a blocker for people to help. It's what stops me most of the time and I'm conformable with the tools, last time I tried on Windows I just gave up because it was too much work and I only have limited time these days. I'm not sure what the solution here is but I don't know if moving to something like GitHub Markdown or Google Docs is the option, mainly because of it throws away a lot of the work we have already done. Having said that though this is a pain point that might help address some of the community involvement if we can solve it. It's not the only problem though like Alexandre said it's just not fun work at times and it can be hard to even write good docs when that is your job and you have a good platform to do it in.Tim Sutton, one of the QGIS founders, reported:

Our main discussion points in the [QGIS Project Steering Committee] meeting were:

- Current documentation approach is unsustainable (a few hardcore enthusiasts but not enough to cope with the rapid pace of development)

- Inviting contributors needs to be substantially easier - I’m talking at the level of editing a google doc or word doc here. At the very least a GitHub markdown page that is instantly published as soon as you edit it.

- Cameron has had a chat with me about employing technical writers to make the documents more cohesive - I think this is a good initiative but Cameron I think we need to get the fundamental issue of the editing platform sorted out first

- Translations severely hamper our ability to switch to a more agile system (e.g. GitHub markdown based wiki or Google doc) - in the PSC call we want to surface the idea of doing away with translations and leave translation initiatives to outside communities (e.g. local user groups). PostgreSQL etc don't have the overhead of this.

- Our documentation could be easier if the format was more structured - think something like editing a changelog entry here. Again we looked at the PostGIS / PostgreSQL examples here which have a very standardised format.

Stepping back from specific comments about tools and processes, I’m seeing a high effort-to-reward ratio for the external documentation community. Options to address this include:

- QGIS docs core team to absorb the effort, either through funding or inspiring volunteers.

- Help contributors get their content back into the core, likely with hand-holding, or possibly out-sourcing paid work to them.

- Improve the efficiency of tools or improve our explanation of tools. While improved tools will be helpful, I think it is a generic problem faced by the whole open-source community. As such, I feel QGIS should reach out to the greater community to help solve it.

- Merge disparate documentation.

- Increase doc quality from “verbose and okay” to “intuitive, obvious and concise”.

QGIS Community questionnaire about docs

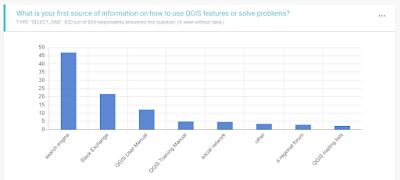

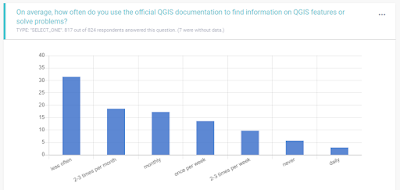

824 people answered a questionnaire about how you learn about QGIS. Anita Graser compiled results into the following tables.Tom Chadwin summarised the results as:

Questions 1-4 (quantitative)Paolo Cavallini argued:

Question 5 (qualitative)

- 70%’s first-choice is Googling/StackExchange, which dwarfs the < 20% choosing official docs

- The fact that Googling came top of search methods emphasizes that we need to pay attention to SEO in the official docs

- Fewer than 50% find their answers in the official docs “often” or “always”, 45% answering “sometimes”

- Official docs are underused – over 50% only consult monthly or less frequently (including “never”)

- Many find the official docs too abstract, and would prefer examples worked in

- Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is a lot of enthusiasm for video tutorials

- There is some criticism of the confusion of QGIS versions in the documentation, especially when deep-linked from a Google result

To me this confirms my opinion: our manuals are of limited relevance to the community of users. IMHO we have two options here:Summarising Alexandre Neto's longer analysis:

Quite frankly (sorry, no offense for the huge and excellent work done until now), I do not see a realistic way of implementing (and, more importantly, to keep always up to date) the first option, so I tend to prefer the second one.

- Re-haul the whole documentation so to make it the real reference.

- Shrink it down to the bare minimum (mostly a list of the commands and functions available), leaving the fancy documentation out in the Wild World of the Internet.

- It's clear that people often search for help a lot.

- In terms of QGIS Docs quality, ... [it] seems that definitely needs improving.

- As a documentation person myself, I naturally have to disagree with the idea that the project should ... simply resign to a shrunk version of the documentation and let the outside world provide the fancy answers to the users. ... IMHO, Good, precise, and updated documentation leads to more adoption and better user experience.

- An interesting fact: in two weeks open to answers, ... this questionnaire gathered more than 800 responses! To me, this alone says a bit about the importance that documentation has for our users.

Documentation best practices

I'm concerned people are searching for one approach to documentation when there should be multiple. In a highly regarded article in Tech Writing circles, Daniele Procida argues:There is a secret that needs to be understood in order to write good software documentation: there isn’t one thing called documentation, there are four.

They are:

They represent four different purposes or functions, and require four different approaches to their creation. Understanding the implications of this will help improve most software documentation - often immensely. ...

- Tutorials,

- How-to guides,

- Explanations, and

- Technical references.

The audience for different doc-types have different needs:

- API References need to be accurate, unambiguous and up-to-date. Polish is a nice-to-have.

- Community forums are great for niche topics. Incorrect or dated information is tolerated.

- Quickstarts need to be accurate and polished, but need not reference the latest Bleeding Edge release. Aligning with the Long Term Release is acceptable.

Matteo, what to focus on

Matteo from the core QGIS documentation team who volunteered to mentor QGIS Season Of Docs writers suggested:- I really think that currently, we need to define precise roles (issue manager, reviewer, English reviewer, etc). IMHO the growing complexity of the last years made it difficult for us to convince other people to contribute (at least, I'm not able to convince people during training and other activities)

- +1 for the "community" evangelist (could be another role of above)

- -1 to change the framework (even if complex is too important)

- -1 to create other dedicated repositories with additional training material: just add another chapter to the existing manual

Summary: without boring everyone that already knows the current situation, I really think we have to set up a clear workflow (for us [the QGIS documentation team] and newcomers) or else we will lose volunteers and other people that want to contribute to the project.

Andreas, Paulo and Tim, considering funding

Andreas Neumann, Paolo Cavallini and Tim Sutton weighed in on funding tech writers:- Andreas: It is not primarily a problem of finding financial resources. Every year we assigned funds for documentation and in most years those funds haven't been used. Even if we would make more funds available to the team, I feel this wouldn't solve the problems the team is facing.

- Paulo: While I agree that we should keep on using our funds, and additional resources, as an incentive for documenters, I think this should be done with a clear plan in mind. If not done carefully, this move could discourage volunteers, not only in this area ("why should I volunteer, when another one is doing the same thing and is paid for this?"). Volunteer communities are hard to build, and easy to destroy. Replacing volunteers with employees can quickly become very expensive, and we should be sure we'll be able to raise enough money both in the short and in the long term to fully support the effort. I suggest working out a budget for this, to check how feasible this solution can be, before taking further steps.

- Tim: I have a different opinion on this. Based on our experience of paying developers I don’t think it has in any way reduced the volunteer contributions to the code base - on the contrary, it probably has incentivised those that we paid to donate lots more of their time. I am pretty sure that we will have similar experience in other areas of the project. I am more bullish on documentation and think that we should work enthusiastically to get one or more dedicated, full-time document writers in the QGIS project….over and over we here it is the most wanting part of the project.

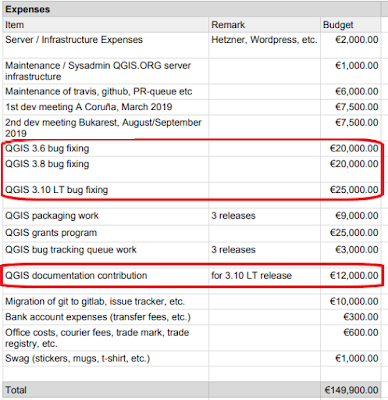

|

| 2019 QGIS Budgeted expenses |

- The QGIS team run on an incredibly small and efficient budget. Strategic investment from external stakeholders should yield a significant return-on-investment.

- Programmers' daily rates were higher than tech-writers'. This concerns me as I question whether tech-writers' employed are suitably experienced. Typically, a good tech-writer is a programmer who has learned to write, or a writer who has learned to program.

- The €12,000 allocated to documentation won't go far if paid at standard tech-writer rates.

- Bug fixing (for programmers) was allocated five times more than docs (for writers).

Clarence, finding writers

To find writers, Clarence Cromwell, a tech writer, suggested:

Why don’t you reach out to the WriteTheDocs community. It has a slack group which includes a #job-posts-only channel. I’ve seen many budding tech writers asking how to break into tech writing. You could offer to mentor writers in git and software processes, in return for a review of documentation.

This is worth pursuing in order to bolster our existing tech writing team. However, for holistic documentation leadership, I feel we need more than individuals can provide on volunteer time alone. We could consider Google’s SeasonOfDocs model of paying a stipend (for a lead tech writer). Note: I feel this role needs sustained sponsorship; Google’s sponsorship is limited to three months.

Anne and Charlie’s research into open source success factors

There are insights from open-source research we can draw upon. Pertinent to this conversation is Charlie Schweik’s research into open source success factors and Anne Barcomb’s research into episodic volunteers. Their research highlights:Factors which lead to a project’s success are:

- Leadership by doing.

- Clear vision.

- Well-articulated goals.

- Task granularity: Projects have small tasks ready for people who only can contribute small bits of time.

- Financial backing.

- Although Open Source episodic volunteers were unlikely to see their participation as influenced by social norms, personal invitation was a common form of recruitment, especially among non-code contributors.

- Episodic volunteers with intrinsic motives are more likely to intend to remain, compared to episodic volunteers with extrinsic motives.

- Episodic volunteers derive satisfaction from knowing that their work is used, enjoying the work itself, and feeling appreciated.

- Lower barriers to entry.

- Provide opportunities for social interactions.

Learning from the OSGeoLive experience

I think it is worth considering the formula used in the OSGeoLive project to attract hundreds of episodal contributors, many of whom have been working on docs. It is summarised here:- Start with a clear and compelling vision; inspiring enough that others want to adopt it and work to make it happen.

- This should be followed by a practical and believable commitment to deliver on the vision. Typically this is demonstrated by delivering a “Minimum Viable Product”.

- Be in need of help, preferably accepting small modular tasks with a low barrier to entry, and ideally something which each person is uniquely qualified to provide. If anyone could fix a widget, then maybe someone else will do it. But if you are one of a few people with the skills to do the fixing, then your gift of fixing is so much more valuable, and there is a stronger moral obligation for you to step up.

- Ensure that every participant gets more out of the project than they put in.

- Avoid giving away free rides. If you are giving away something uniquely valuable; and it costs you time to provide that value for your volunteers; then it is ok to expect something of your volunteers if they wish to get something in return.

- Use templates and processes to facilitate domain experts working together.

- Reduce all barriers that may prevent people from contributing, in particular, by providing step-by-step instructions.

- Set a schedule and work to it.

- Talk with your community regularly, and promptly answer queries.

- And most of all, have fun while you are doing it. Because believe you me, it is hugely rewarding to share the team camaraderie involved in building something that is much bigger and better than you could possibly create by yourself.

My assessment

The QGIS documentation community appears overwhelmed and seems to need help with:- Articulating doc challenges to the community, potential contributors, and potential sponsors;

- Defining a clear vision and roadmap;

- Coordination and project maintenance;

- Breaking large daunting challenges into small tasks that can be tackled easily by volunteers;

- Capturing community good-will and offers of assistance,

- Inviting people to get involved one-on-one and then mentoring them;

- Periodic catchups;

- Outreach and evangelising;

- Attracting satellite initiatives into the core;

- Keeping up with a rapidly innovating software baseline;

- Documentation tooling and processes;

- Sustaining initiatives, and orphaning unmaintained documentation.

Suggestions

These suggestions are presented in my proposed order of priority.1. Community evangelist / coordinator

I believe QGIS should engage a “community evangelist and coordinator”, tasked with:- Inspiring others.

- Capturing untapped goodwill from within the QGIS community and potential business sponsors.

- Embracing and extending QGIS’s supportive culture.

- Reaching out one-on-one and personally inviting people to join, then pro-actively supporting them during their onboarding experience.

- Helping to reduce barriers to entry.

- Defining and managing a roadmap, with milestones and schedules.

- Coordinating community collaboration.

- Supporting documentation development, deployment and reviews, as required.

- Is friendly, approachable, and community-minded.

- Is likely a notable and experienced member of an open-source community, whose opinions are respected and hold weight within the community.

- Is technical enough that they can help a newbie with git and doc tools.

- Is business savvy and able to persuade business people about the value of collaboration.

- Presents competently at conferences.

Sustained funding should be sourced for this role as it will be difficult to resource on volunteer labour alone.

2. Vision and roadmap

Common feedback from volunteers was not knowing how to give back. We appear to be lacking the vision and roadmap which open-source research suggests is important. Alexandre Neto noted:- Unfortunately, this issue list is the only thing we have [re roadmap].

3. Information architecture review

I get the impression that QGIS documentation is quite good, but it hasn’t been audited by a senior technical writer/information architect. I suggest a senior information architect be engaged for a once-off engagement to set up QGIS’s approach to documentation. We should consider:- Best practice document types, templates and writing styles, tailored for different target audiences.

- Documentation architecture.

- Quality expectations.

- Maintenance strategy.

4. Engage a technical writer

People from the core doc team have noted that much of the QGIS documentation is written by software developers, or power users (without formal writing training). For many, English is a second language.I suggest a sustained technical writer role be set up to:

- Reviews all new documentation generated by the community.

- Work with the authors to ensure it fits with QGIS’s writing guidelines and quality standards.

5. Attract external QGIS docs into the core

There has been discussion about the significant amount of external docs and training material which is not coming back into the core QGIS. I’d suggest:- Publicly stating the value we place on internal rather than external documentation.

- Encourage sponsors, and those paying for training to make use of internal rather than external material.

- Reach out to external material providers and work with them to bring their material back into the core. Acknowledge extra effort required to do this. (It will be short term pain for long term gain.)

- Monitor community activity and opportunistically support people to bring their external docs back into the core.